A 20-minute community is not a limit on choice, but an expansion of it. It is about giving our cities, towns and neighbourhoods back to the people who form them.

‘What is a city?’ asked William Shakespeare in Coriolanus. His answer: ‘the people’. He was right. Cities and towns are not ends in themselves, nor a convenient way to socially organise populations, but an expression of the particular people who live in them, their needs and desires and ways of life. That doesn’t sound like such a radical idea today, in fact it is almost a platitude among urbanists, but a glance at the history of urban planning, especially the errors of the 20th century, makes it obvious that it is an idea that is not always well understood.

Now that we are faced with a huge new challenge, the existential threat of climate change, we are being forced to think again – and with renewed ambition – about how we make thriving places. It is a good time to ask ourselves whether we have really taken Shakespeare’s insight to heart. Can we decarbonise without dehumanising?

the 20-MINUTE COMMUNITY

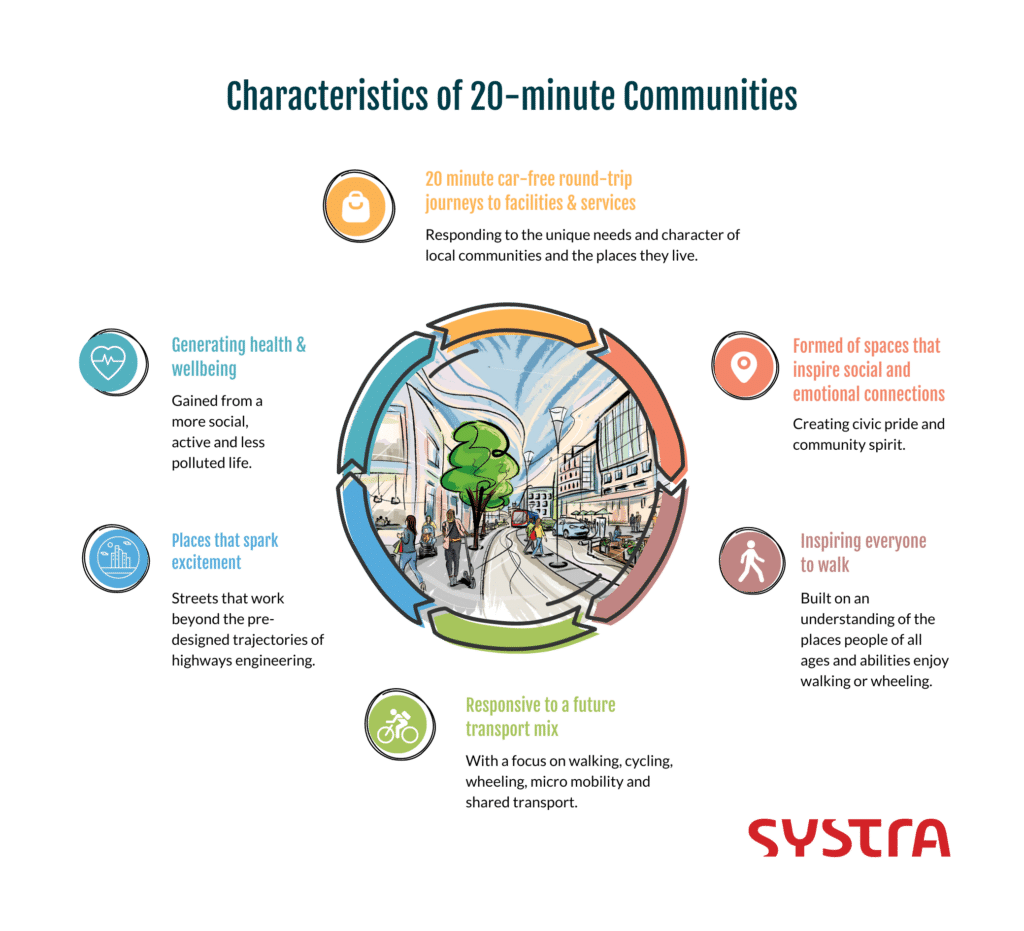

The 20-minute community – the idea that in an urban area all residents should be no more than a 20-minute car-free round-trip from essential facilities and services – is the affirmative answer to that question. But achieving such a vision will require more than deep changes in how planners, policy makers and administrators work and think.

It will mean breaking through walls of suspicion and distrust from people who have reasons to be wary of those with clipboards.

After all, many of the problems in urban design we face today – the things that are driving the carbon crisis such as zoning by function, prioritisation of car travel, parking issues, highways and the centralisation of facilities – are products of past planning decisions that were often imposed on local communities by well-meaning professionals with the best intentions at the time.

The recent upsurge in anger and protest against interventions such as Low Traffic Neighbourhoods (LTNs) is an indication of the depth of suspicion that exists about planning interventions, and the deep attachment that many people feel towards their cars and the ways of life they have built around them. The media – and social media in particular – is suddenly awash with conspiracy theories about 20-minute neighbourhoods and their 10- and 15-minute siblings.

It is tempting to mock the idea that improved walkability, better connectivity and reduced parking could be the cover for a sinister new world order, but we should not be too quick to dismiss the power and depth of these emotional connections or misunderstand why they matter to people.

When we change how places work, we are changing ways and patterns of life which have deep meanings for the people who live them..

GIVING THE PLACES BACK TO THE PEOPLE

We need to demonstrate and communicate that a 20-minute community is not a limit on choice but an expansion of it. It is not about removing agency but adding it, giving our cities, towns and neighbourhoods back to the people who form it.

Rachel Kyte, Vice President of the World Bank, has remarked that ‘the question that should shape the debate on climate action [is] how exciting is it going to be to live in low carbon cities?’ The 20-minute community is a return to the excitement of place because it frees us to explore and refine our own urban geographies beyond the pre-designed trajectories of highway engineering.

This presents a difficulty for transport planners dedicated to improving walkability, of course. Although our data on why and where people choose to walk is getting better, walking is still much more unpredictable and contingent than other transport modes – and so harder to plan for – but these are technical challenges that we are well placed to meet.

The more immediate challenge is convincing populations that low-traffic, low-carbon, dense, decentralised, walkable, active travel towns and cities are what they want.

QUALITY MATTERS

That means demonstrating that we understand that proximity and availability are not the only defining characteristics of a 20-minute community. Quality matters too. The spaces between where we begin and where we are going is where life happens.

It won’t happen if the place is threatening, polluted or difficult to navigate, no matter how close A is to B. In the past, places developed organically around local facilities and services – church, pub, shop – following the desire lines of homogenous populations over centuries. It gave us places that, hundreds of years later, still attract people with their charm and liveable qualities

Industrial modernity put a stop to that, and we can’t return to it, but we can do the next best thing which is to identify the needs and desires of communities by engaging with them, understanding that their needs are idiosyncratic and specific. All populations are multi-grained and if we are claiming to put everybody within 20-minute reach of all the services and facilities they need, we had better understand what those are.

Access to a post box, for example, may not be a majority need but is a lifeline for some members of the community. It is the sort of thing that transport planners can find hard to ‘see’ unless we ask carefully and early in the process.

It is undisputedly this type of process which hasled to widespread trialling of ‘mobility hubs’ which can bring together alternative transport modes – public transport, e-bikes, scooters, EV charging and active travel options – with community facilities in spaces specifically designed to improve the public realm for all.

SYSTRA’s Movement and Place Team embodies these considerations, recognising that transport and placemaking are aspects of the same activity. When we put transport experts with different strategic backgrounds together – transport planners, urban designers, civil engineers, landscape architects, social scientists, health, environmental and education specialists – we can more easily work towards a concept of planning that keeps the idea of the dynamic person-centred place more firmly in view. This also resists the natural tendency towards treating each aspect of project planning as a separate technical challenge which all too often ignores social and community dimensions.

CREATING A VISUAL MATRIX

Not that technical challenges don’t matter. Of course they do, and we need better tools to solve them. Planning projections that map distance between points of departure and services in an area are widely used in various forms but can be insensitive to the significant difference between ‘crow flies’ approximations of journey length and real on-the-ground route formations.

SYSTRA’s approach is to respond more directly to the urban fabric and quality, using real journey data, and to represent that information not just as a series of scores but as a visual matrix, a map of interconnectivity by time. This is a far more intuitive approach than just another ‘data-in-data out’ black box. Using the matrix map, all stakeholders can more easily envisage where facilities might need to be enhanced, a street pattern altered, or a constraint such as a railway line overcome

It situates transport as part of the fabric of a place rather than just another structure within it. It is a way of thinking about places, not simply a tool for ordering priorities. Tools like these can help address thorny problems such as how to masterplan for 20-minute communities in developments that have to scale up in stages, sometimes from an initial development of tens of dwellings to a final development of thousands. They situate the process in a framework that is always focussed on place-building no matter how powerful the counter currents of other commercial incentives might be at any stage of the project. It is only by keeping that idea of place alive at all times that we can avoid the mistakes of the past, mistakes that will be paid for the negative impact of climate change.

Jane Jacobs, a journalist, activist and campaigner credited with saving New York’s Greenwich village from the highway-centred developers of the 70s, described cities as ‘immense laboratories of trial and error, failure and success’. Less pithy than Shakespeare, perhaps, but driving at the same thing. Successful cities and towns are formed over time in response to the needs of their populations and that is where they get their energy and life

Not everything works; and that is OK if there is space to respond and to change and learn from the mistakes of the past. The 20-minute community builds in that space if we do it right. We all live in our own separate geographies and these are layered and overlapping. The 20-minute community doesn’t lock anyone into a single mode of life but adds layers to the fabric.

THE CAR LOSES ITS DOMINANCE

The car loses its dominance but doesn’t disappear. In fact, even drivers gain when more people choose to cycle and walk as congestion decreases along with all its stress. Some people will always rely on their car, of course. Yet, how we use cars will change over time, car ownership may reduce outside of cities too as we begin to hire or share cars more, as proven in our larger cities. Electric vehicles and how we charge them will be part of the future transport mix. But if we can build places that tempt people out of their cars instead of only coercing them, we can turn the energies that are currently being wasted on campaigning against LTNs and temporary bike lanes into something positive.

We can open the door to the discovery of advantages that go far beyond the gains in health that a more active and less polluted life brings. We can highlight the deeper social and emotional connection with home. The pleasures and excitement of chance meetings and discoveries. The simple joy of more human connections – and more opportunities to live our lives.

Australia

Australia  Brazil

Brazil  Canada

Canada  China

China  Denmark

Denmark  France

France  India

India  Indonesia

Indonesia  Ireland

Ireland  Italy

Italy  Malaysia

Malaysia  New Zealand

New Zealand  Norway

Norway  Poland

Poland  Saudi Arabia

Saudi Arabia  Singapore

Singapore  South Korea

South Korea  Sweden

Sweden  Taiwan

Taiwan  Thailand

Thailand  United States

United States  Vietnam

Vietnam