Human Factors (HF) is often thought of as ’all about the individual’; what they do, how they feel, why they did or didn’t do something.

However, this only matters with the added context of where individuals sit within a wider system. In application HF is much broader. It considers how people interact with their working environment, with other people, with technology and within their organisation. Our Human Factors team are experienced in working with different user groups to identify and capture their wants and needs from the system in which they sit.

This article reports on a ’Design for Accessibility’ piece of work that the UK HF team presented at a Design for Safety event at Heathrow Airport (London). It also discusses how HF can go even further in supporting accessibility and inclusion, by thinking beyond the protected ’known’ characteristics and questioning existing constraints that prevent a wider demographic of people from performing certain tasks or job roles.

WHAT IS ACCESSIBILITY?

When it comes to people, there is no such thing as ’normal.’ Historically, accessibility has been a term used to describe the systems, products and services that are designed to be usable by those with disabilities. In this context, disabilities have been thought of by designers as a personal health condition. With this approach, design solutions can easily be viewed as ’inclusive’ or ’exclusive’ , with inclusive design being where we want to get to.

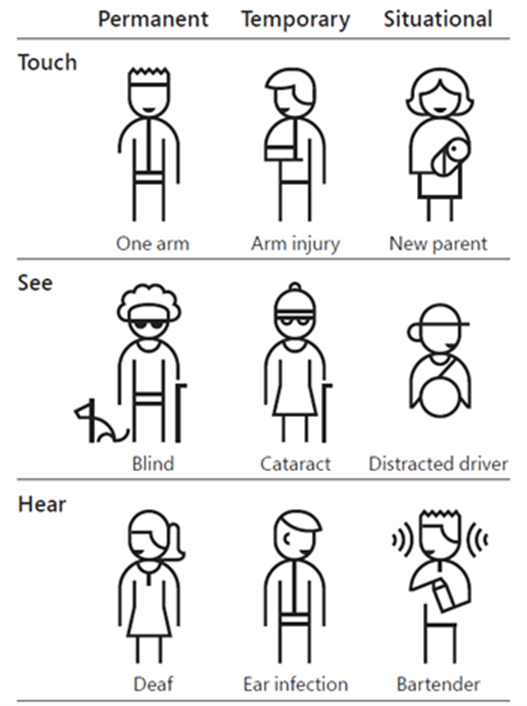

Taking a forward-thinking approach, accessibility relates to a mismatch between an individual and an interaction. Whether that be in the workplace, using public transport, grocery shopping or changing a fuse at home. This definition allows us to explore how any one person can experience a mismatch at one time in their life and promotes that accessible design is good design for all (Figure 1).

“By designing for someone with a permanent disability, someone with a situational limitation can also benefit. For example, a device designed for a person who has one arm could be used just as effectively by a person with a temporary wrist injury or a new parent holding an infant” – Microsoft Inclusive Design

EQUALITY, DIVERSITY AND INCLUSION (EDI)

Using the Chartered Institute of Ergonomics and Human Factors (CIEHF) EDI guidance definitions, equality is concerned with fairness, diversity is concerned with representation, and inclusion is concerned with involvement. The CIEHF guidance describes how taking a HF approach can help to mitigate some of the specific EDI challenges arising from the protected characteristics defined in the UK’s Equality Act (such as Age, Disability, Gender Reassignment, Pregnancy and Maternity). Not only this, but the guidance outlines how more can be done to look beyond protected characteristics (such as socio-economic backgrounds), to recognise ’hidden disabilities’ (such as colour blindness) and to recognise capability loss (such as dexterity, mobility and reach).

As HF specialists it is important that we continue to push the agenda on thinking beyond protected characteristics, to get a truer representation of the requirements for end users.

INSTILLING EMPATHY IN DESIGNERS

It can be challenging to empathise with users whose attributes, and the experiences attached to them, are so different from our own; but the biggest step change is to acknowledge that they exist. We need to challenge our assumptions, inform our clients and encourage designers to explore the ’unknown unknowns’ at the earliest stage in the design lifecycle.

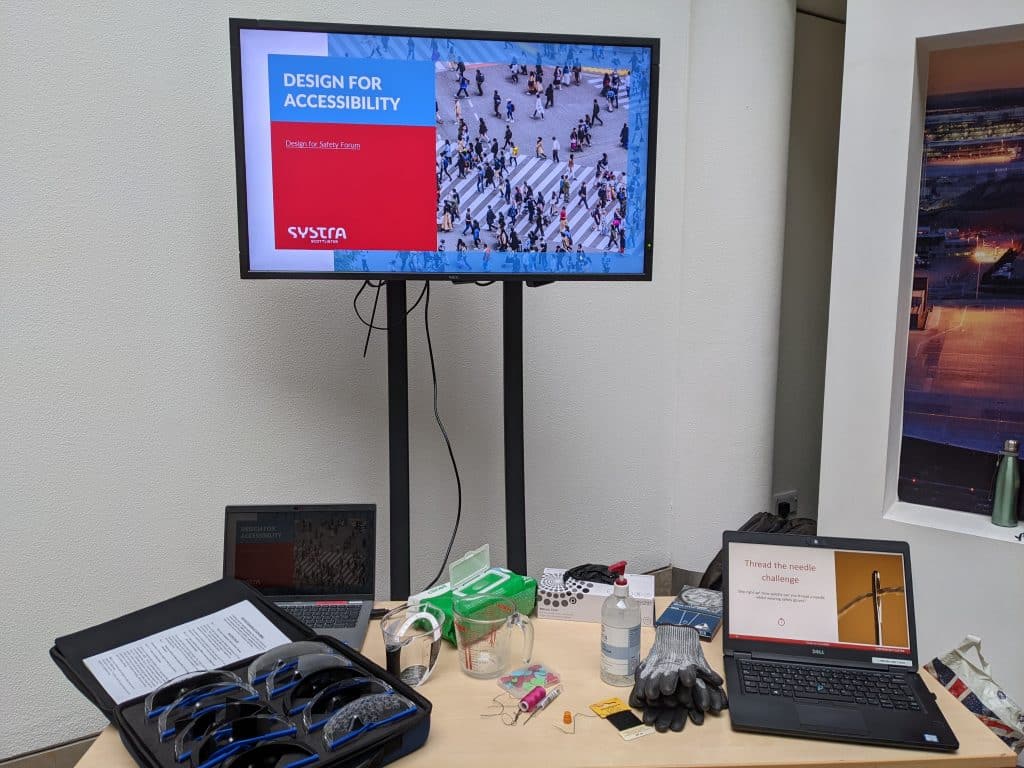

For the Design for Safety event at Heathrow we put together an empathy toolkit for stakeholders. The purpose of the toolkit is to enable stakeholders to quickly understand the difficulties faced by people with accessibility mismatches and how early consideration and intervention can mitigate the risk of exclusion.

The toolkit includes:

- 10 pairs of spectacles (Figure 2); simulating the most common symptoms of the most common eye conditions (e.g., tunnel vision, loss of visual acuity, retinal degeneration)

- Safety gloves; typically warn in safety critical environments such as railway maintenance

- Darning needle and thread.

We asked attendees on the day to perform a task as simple as threading a needle. Volunteers were asked to perform this in three different conditions:

- Thread the needle;

- Thread the needle wearing safety gloves; and

- Thread the needle wearing safety gloves and a pair of vision impairment spectacles.

Perhaps unsurprisingly, the time required to perform this dexterous task increased with each layer of complexity. Not only was this approach engaging, but it also provoked discussion and allowed stakeholders to link these mismatches to their own working life and to the working lives of those whom they design for. Stakeholders could relate their frustrations to their own experiences (such as ill-fitting PPE that has not been designed for women) and to invisible impairments (such as a sensory loss of touch.) It also helped to demonstrate how individuals may have more than one impairment and that multiple impairment can exacerbate the challenges that they face.

LET’S NOT BE CONSTRAINED BY HISTORIC DESIGN

So often we are constrained by what came before. In other words, designing ’how it has always been done’ and ’for a demographic of people who have always done it’. This affects everything, from the job design itself, to the written processes supporting the job, and the equipment that is used to perform the work. Designs today are all based on the evolution trajectory of what came before. We are missing a trick by not considering how we can get more people doing more things!

Conclusion

Designing for accessibility should not a tick box exercise to meet minimum legal requirements for protected characteristics. It should proactively design for mismatches between individuals and interactions that will benefit all end users, not just those who have a permanent impairment. Empathy is a key driver in demonstrating challenges that individuals face and how our design input can mitigate those challenges. The more we can adopt this approach and educate stakeholders in the design process, the better the end solutions will be for accessibility, equality, diversity and inclusion.

Brazil

Brazil  Canada

Canada  China

China  Denmark

Denmark  France

France  India

India  Indonesia

Indonesia  Ireland

Ireland  Italy

Italy  Malaysia

Malaysia  Norway

Norway  New Zealand

New Zealand  Poland

Poland  Saudi Arabia

Saudi Arabia  Singapore

Singapore  South Korea

South Korea  Sweden

Sweden  Taiwan

Taiwan  Thailand

Thailand  United Kingdom

United Kingdom  United States

United States  Vietnam

Vietnam